Breaking Basta: Insights from Black Basta’s Leaked Ransomware Chats

Key Takeaways

During the period covered by the Black Basta leaked chat logs (18 September 2023 – 28 September 2024), we observed the following

- We observed at least 47 cryptocurrency wallets associated with Black Basta, which we tied to the equivalent of $38 Million USD in transactions.

- Black Basta operators depended on open-source information in understanding potential victim profitability, using ZoomInfo to determine the notional revenue of victims and likely setting ransom demands as a percent of these figures.

- Black Basta operators leveraged ChatGPT and internal scripts to socially engineer victims, both at the outset of an incident to gain initial access and to reduce the likelihood of detection post-foothold.

- Black Basta operators repeatedly discussed vulnerabilities with openly available Proof-of-Concept exploits, making them easier to adapt and leverage in operations. The majority of these vulnerabilities centered on initial access and code execution, and included vulnerabilities not previously attributed to the group.

Introduction

On 11 February 2025, a large JSON file purporting to contain internal Matrix chat logs of the ransomware group Black Basta was posted by a user under the name “ExploitWhispers” on the file sharing site “MEGA” and later posted to a dedicated Telegram channel.

The logs, which cover the period of 18 September 2023 through 28 September 2024, appear authentic, and reflect operational details that the GRIT team has been able to verify as authentic from historical incident response cases of the GuidePoint Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) team, open-source intelligence, and intelligence-sharing partnerships. The chats offer a rare opportunity to “glimpse behind the curtain” into the daily discussions, operational details, and tradecraft of the Black Basta group at a scale not seen since similar leaks spelled the downfall of the Conti ransomware group in 2022. In an oddly familiar scene, Black Basta is assessed to have originated from former Conti team members; whereas Conti disassembled following internal conflict regarding the Russia-Ukraine conflict, this leak appears to have followed internal disagreement over targeting of Russian organizations.

At the time of this blog, Black Basta has not posted a new victim to their data leak site since early January, and its known public-facing infrastructure on Tor has been offline since late January. While we cannot definitively say that the group is now defunct, we assess that the leak has at a minimum, dealt the group a substantial operational setback.

Given the size of the chat logs, we have not yet had the chance to fully unpack all of its content; however, in the interest of time and sharing our findings with the threat intelligence community, this blog presents early findings of note following our initial triage. Broken out below are several segments on topics of significance, including the following:

- Analysis of observed cryptocurrency wallets, associated transactions potentially indicative of ransom payments, and a comparison against observed victims claimed by Black Basta during the time period covered in the logs.

- Analysis of tooling referenced by members of the group

- Analysis of the group’s discussion of the DarkGate malware, and it’s possible relationship to Black Basta

- Analysis of vulnerabilities and exploits referenced by members of Black Basta

- Analysis of social engineering techniques employed by Black Basta

Cryptocurrency Wallets and Transactions

In reviewing the Black Basta chat logs, we initially identified 94 likely Bitcoin wallets by Regular Expression. Of these, we removed the following from consideration:

- Wallets with no associated transactions.

- Wallets associated with multiple transactions; we deemed these as unlikely to represent ransom payments based on the size of the transaction and based on the group’s tendency to generate a “fresh” wallet for ransom payments.

- Wallets associated with small transactions; we deemed these as unlikely to represent a ransom payment based on the size of the transaction, which were below $10,000.

- Wallets that we deemed to be outliers based on transaction size and our final data set, all of which were less than $30,000

This resulted in a total of 47 wallets we assessed as associated with likely ransom payments. We solidified our assessment of these wallets based on shared characteristics present in the overwhelming majority, which included the following:

- “Fresh” wallet usage without prior historical transactions preceding the suspected ransom payment.

- Singular usage of the wallet to receive one transaction and send one transaction, typically within hours on the same day; this indicates likely forwarding of funds to secondary wallets or mixer services.

- Payments from originating wallet addresses ranging from approximately $47,000 to $38,000,000 in Bitcoin

Because Bitcoin transactions work with Unspent Transaction Outputs, each wallet we extracted represented one of two wallets on the receiving end of a transaction. While we would expect that the extracted wallets represent the wallets controlled by members of the leaked chat, in several cases we noted transactions to the wallet of trivial amounts, frequently in the range of 3% of the initiated transaction. Because of this, we cannot rule out the possibility that so-called “change addresses” or “change wallets” were presented in the chats as an operational security measure. Because we cannot definitively tell which wallets represented change wallets vice destination wallets controlled by Black Basta members, we have included figures for both sets in our analysis.

| Lowest Amount | Average Amount | Highest Amount | Total Amount | |

| Sent Transactions – USD (equivalent at time of transaction) | $42,831.87 | $788,751.74 | $8,035,138 | $38,648,835.33 |

| Sent Transactions – BTC | .46707 BTC | 8.61016893 BTC | 87.71 BTC | 421.89827745 BTC |

| Received Transactions – Observed Wallet – USD (equivalent at time of transaction) | $18.34 | $232,161.49 | $3,509,965 | $11,375,913.11 |

| Received Transactions – “Change Wallet” – USD (equivalent at time of transaction) | $358.05 | $556,568.94 | $4,821,031 | $27,271,877.91 |

Based on this review, we can conclusively say the following based on the sample size:

- From 18 September 2023 through 7 November 2024, Black Basta very likely received between $11,375,913.11 and $38,648,835.33 in payments to the identified wallets under the group’s control. Over the span of the 416-day window we analyzed, this equates to between $27,345.95 and $92,905.85 per day in illicit revenue.

- These payments averaged between $232,161.49 and $788,751.74, and a payment received every 8.85 days.

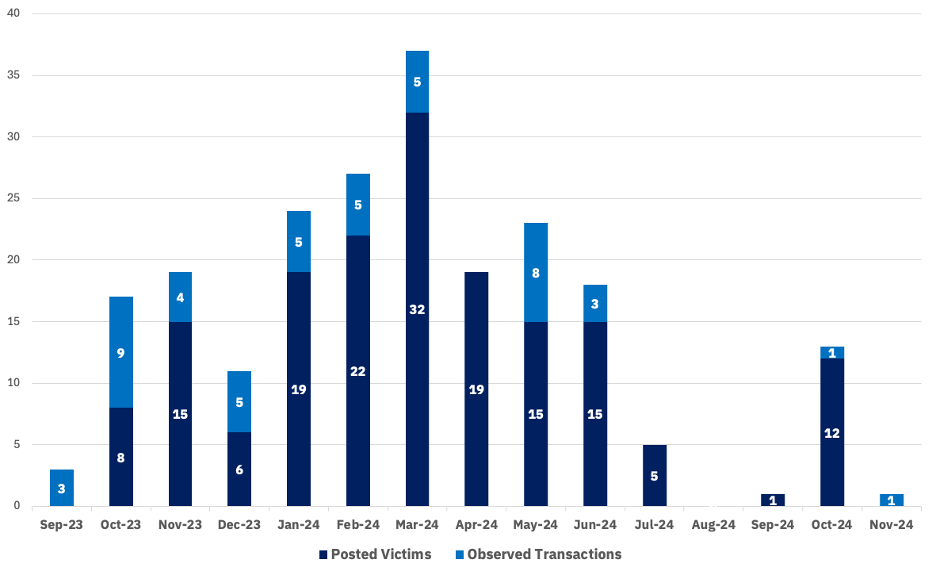

For perspective, we opted to compare these transactions, which we assess to represent at least 47 paying organizations against observed victim posts from the group during the same period of time; while this is not a 1:1 comparison because victims are typically posted weeks or even months after attacks whereas payments may occur more quickly, we believe that our data provides an accurate sample size for comparison. In the same period of 18 September 2023 to 7 November 2024, we observed 169 victims posted by Black Basta to the group’s data leak site. On this basis, we can assess with moderate confidence that during the same period, Black Basta performed at least 216 attacks. Across 416 days, this amounts to an average of .52 attacks per day by the group during this period. To summarize the ratio of observed transactions to observed victims, the below chart visualizes the relationship:

Services and Tooling

As part of our analysis, GRIT reviewed the messages within the leaked chat logs for references to specific tools and services that may have been used by the group. By reviewing for URLs, URIs, and file names, we were able to determine the following:

- When transferring files, either between group members or with victims, Black Basta tends to use low reputation services that specifically offer ephemeral storage, almost certainly for operational security reasons. GRIT identified five services primarily used for this purpose: temp[.]sh, file[.]io, gofile[.]io, dropmefiles[.]com, and transfer[.]sh. Black Basta members shared 802 total unique links to these services in the context of the leaked messages. We observed the actors using these services for transferring malware, exploit proofs of concept, and even decryptors meant for paying victims.

- Many researchers have already noted the extensive use of the services such as Crunchbase, ZoomInfo, or similar business intelligence sites by ransomware threat actors to gather corporate information and inform the setting of initial ransom demands. Observed URLs reflect Black Basta’s heavy use of ZoomInfo to determine the reported revenue of victims when determining their initial ransom demand. Except for one instance in which the similar site “Datanyze” was referenced, the chat members appear to have used ZoomInfo exclusively. Though we do not know whether the members of the chat researched during the reconnaissance phase or only upon affecting a successful intrusion, we observed 367 unique ZoomInfo URLs reflecting actual or potential targets of the group between 18 September 2023 and 28 September 2024.

- We observed members of the chat using common internet intelligence search engines such as Shodan and Censys throughout the chat logs throughout. Use of these engines appeared to have focused on detecting vulnerable exposed infrastructure, particularly in the wake of newly publicized vulnerabilities and associated Proof-of-Concept (PoC) exploits. We also observed the chat’s members using the same services to inspect their own infrastructure, presumably to validate operational security and evade detection. Across the totality of the leaked messages, GRIT observed 24 unique links to Shodan and Censys.

- In reviewing the day-to-day operational messages, we repeatedly observed expressed concerns by the chat’s members of multiple security products and their ability to detect the group’s malware. The group’s sentiments, which ranged from apparent frustration and sarcasm to begrudging respect, highlight the continued barriers of such products to the group’s successful operations, particularly in cases where substantial time and resources may have already been expended. In an attempt to evade or circumvent these tools, we observed the chat’s members using malware analysis and sandbox tooling including VirusTotal, Hybrid-Analysis, and Joes’ Sandbox. We also observed the use of Filescan[.]io and Scanner[.]to, with the latter seemingly the favorite of the group having been tested against 52 unique files. While referencing these services, the actors tended to either upload the malware themselves, or reference samples presumably uploaded by their victims. In some instances, the actors checked the same sample multiple times to determine if a particular piece of malware or script had obtained a higher detection rate. In all, GRIT observed 64 unique instances of links to malware scanning services.

DarkGate and LLM Usage

DarkGate. A review of the leaked chats revealed a strong reliance on the DarkGate loader malware. A connection between Black Basta and DarkGate has been corroborated in various reports, but the level of interest shown by the group’s members in DarkGate stood out as pronounced throughout the chat’s timeline; while often referenced obliquely, DarkGate is referenced directly in a 22 November 2023 message, when the user nn asks “What is DarkGate“ and is soon answered by GG with the translated response “the second lider that we use…We are using two Loaders mine and Dargate to work now”. Chat member lapa also discusses the group’s builds of DarkGate on multiple occasions, specifically inquiring as to whether they are detectable against malware repositories. The chats demonstrate several instances of lapa sharing threat detection signatures with other members of the chat, immediately followed by troubleshooting instructions on how to circumvent such detections.

ChatGPT. We also observed the chat’s participants referencing ChatGPT. In one example on 21 February 2024, the actor nn recounted their use of the LLM tool during an attack to support social engineering, where “there the person [thought] something not okay When I got into a computer. Started panic opened… I quickly CHAT GPT subsided and asked me to write a fake letter plausible.”

Upon encountering issues with the domain controller, a thorough examination of the hosts was conducted by a specialized technical professional. The investigation encompassed an in-depth scrutiny of the network infrastructure, focusing on the integrity and functionality of each host within the domain. This encompassed a meticulous review of network configurations, system logs, and performance metrics to identify any anomalies or irregularities that could potentially impede the domain controller’s operations. The examination was executed with meticulous attention to detail, employing diagnostic tools and methodologies tailored to the specific nuances of domain controller operations. Through this comprehensive analysis, the technical specialist sought to pinpoint and rectify any underlying issues affecting the stability and performance of the domain controller, thereby ensuring the seamless operation of the network environment.

The tool likely allowed the actor to display the properly written message to whomever discovered their intrusions and may have calmed any initial reaction by the victim, allowing the actor to continue their intrusion.

Vulnerabilities

This section examines the most discussed vulnerabilities within the leaked chats, contrasts them with confirmed exploitation reports, and analyzes the group’s broader strategy. Our review of the leaked chats suggests that while Black Basta prioritizes Initial Access and Execution techniques, there is a notable discrepancy between the vulnerabilities the chat’s participants discuss and those publicly attributed to the group as having been exploited “in the wild” by security researchers. Furthermore, the data indicates a strong reliance on publicly available Proof-of-Concept (PoC) exploits over zero-day vulnerabilities, with the group demonstrating willingness and ability to adapt PoCs for their own purposes.

The “top 10” most discussed vulnerabilities observed within the leaked chats can be seen as follows:

| CVE | Vendor | Product | Times Referenced | MITRE ATT&CK Category |

| CVE-2024-3400 | Palo Alto Networks | PAN-OS GlobalProtect | 78 | Initial Access (T1190) |

| CVE-2022-27925 | Synacor | Zimbra Collaboration Suite | 42 | Initial Access (T1190) |

| CVE-2024-21762 | Fortinet | FortiGate SSL VPN | 21 | Execution (T1203) |

| CVE-2023-35628 | Microsoft | Windows | 18 | Privilege Escalation (T1068) |

| CVE-2023-36394 | Microsoft | Windows | 18 | Execution (T1203) |

| CVE-2023-36845 | Juniper | OS | 18 | Discovery (T1046) |

| CVE-2024-26169 | Microsoft | Windows | 18 | Execution (T1203) |

| CVE-2024-21413 | Microsoft | Office Outlook | 16 | Credential Access (T1114.002) |

Most frequently referenced vulnerabilities by CVE

Black Basta’s discussions of vulnerabilities frequently centered on CVEs which could enable initial access and execution of code. To this end, the most frequently mentioned CVEs overwhelmingly impacted external-facing applications such as VPNs, email servers, and enterprise collaboration suites. This focus emphasizes the importance of gaining the initial foothold as the beginning of an active intrusion.

In reviewing total mentions of vulnerabilities by associated product vendor, Black Basta discussed Microsoft related vulnerabilities more than any other, with a singular Palo Alto vulnerability coming in second. Surprisingly, Synacor’s Zimbra Collaboration Suite is the third most discussed vendor and product, beating out larger market share vendors such as Cisco and Citrix by a comfortable margin. Additionally, one of the most widely reported incidents attributed to Black Basta – the Ascension Healthcare hack – allegedly involving ScreenConnect by ConnectWise – was discussed by the group a total of 16 times.

| Vendor | Count |

| Microsoft | 174 |

| Palo Alto Networks | 78 |

| Synacor | 51 |

| Fortinet | 26 |

| Juniper | 22 |

| WordPress | 18 |

| Connectwise | 16 |

| Exim | 14 |

| Citrix | 13 |

| Linux | 12 |

Referenced vulnerabilities by product vendor

CVE-2024-3400, a vulnerability in Palo Alto Networks’ GlobalProtect, was the most frequently discussed and has been confirmed via their chats as having been exploited by Black Basta. The internal chat leaks reveal that the group purchased an exploit for this vulnerability and carried out significant troubleshooting to successfully exploit the vulnerability, reinforcing their willingness to leverage the cybercrime-as-a-service ecosystem to gain initial access.

Additionally, high frequency mentions of the Zimbra Collaboration Suite vulnerability (CVE-2022-27925) was unexpected, given that more widely known attack vectors like Citrix and Cisco had fewer discussions. This suggests that Black Basta (and potentially other ransomware operators) could turn to less high-profile networking or security apparatuses as a low-hanging fruit due to its use in smaller enterprises and educational institutions, where security patching may be less stringent.

Another significant finding is that only one of the top 10 most discussed CVEs from the chat logs (CVE-2024-26169) had previously been confirmed in open reporting as actively exploited by Black Basta, based on Broadcom’s reporting in June 2024. In line with frequent assessments that cybercrime threat actors depend heavily on publicly available Proof of Concept (PoC) exploits, a review of 10 CVEs attributed to Black Basta in media reports reveals the frequency with which exploited CVEs and PoCs coincide:

| CVEs | Context | Pub Date |

| CVE-2024-1708 | No POC available | 27-Feb-24 |

| CVE-2024-1709 | POC available | 28-Nov-24 |

| CVE-2020-1472 | POC available | 28-Nov-24 |

| CVE-2021-42278 | POC available | 28-Nov-24 |

| CVE-2021-42287 | POC available | 28-Nov-24 |

| CVE-2021-34527 | Not referenced in Chats / POC Available | 29-Jul-24 |

| CVE-2024-37085 | Not referenced in Chats / No POC Available | 29-Jul-24 |

| CVE-2023-28252 | Not referenced in Chats / POC Available | 29-Jul-24 |

| CVE-2022-30190 | POC available | 30-Nov-22 |

| CVE-2024-26169 | No POC available | 12-Jun-24 |

POC Availability of Black Basta-associated Vulnerabilities

Black Basta seemingly favors publicly available Proof-of-Concept (PoC) exploits. Of the vulnerabilities mentioned by the group that previously been directly attributed to them, only two lack publicly available proof-of-concepts, one of which has reportedly been exploited in conjunction with another vulnerability that does have a proof-of-concept (CVE-2024-1708 and CVE-2024-1709 respectively). This evidence supports contemporary assessments threat actors, and Black Basta in particular, have been more likely to use exploits that have already been publicly disclosed than they are to develop their own novel exploitation techniques, preferring to benefit from the broader security research and exploit development communities than invest in bespoke exploitation techniques. Despite this, we also observed instances throughout the chats in which members discussed the purchase of novel exploits and working with developers to troubleshoot problematic exploits that had previously been purchased, ostensibly to fill gaps in obtaining access where publicly available PoCs could not be sourced.

Social Engineering

As a part of GRIT’s review of the leaked chats, we uncovered evidence of the group’s use of a combination of “email bombing” and social engineering in order to gain initial access to target organizations. Black Basta’s use of this technique has been reported in the past, but thanks to a message sent by the group’s leader GG on 5/23/2024, we were able to obtain an example transcript that reveals the exact tactics by which the group sought to trick unsuspecting users into granting access to their network.

The group first initiates an “email bomb” attack on the target user’s email address, filling their inbox with thousands of emails with the intent of inducing panic. Next, the group makes a phone call to the target user. Impersonating a member of the target’s IT department, the Threat Actor states that they have detected unusual activity and encourages the user to download and install AnyDesk so that they can remediate the issue remotely.

Note: AnyDesk is an otherwise legitimate Remote Monitoring and Management (RMM) tool which Black Basta and many other cybercrime groups use to establish persistence on an endpoint, often without triggering EDR alerts due to its ubiquity and legitimate use case.

Once installed, Black Basta is free to remotely access the impacted machine at any time, granting them a foothold on the network. This approach appears to have been effective for Black Basta on multiple occasions in which the group was not able to achieve initial access to a target network via other means.

The below transcript reflects a likely guide used by the group for social engineering efforts as described above:

Operator: Hello, my name is Owen. I am representing our IT department. I’m calling regarding a current security incident that our company is facing. Do you have a moment to talk? This is an urgent security matter for you and the company.

Client Response: [Waiting for response]

Operator: Thank you for your time. Our security team has identified a massive set of spam attacks against our business. These attacks primarily involve the delivery of malware through phishing emails. We have confirmed that these threats are legitimate, which is why we are calling you to check your systems with us.

Operator: Let me provide some context. Our monitoring tools have identified that these emails are being sent to various targeted addresses, including yours. The emails are crafted to look legitimate, making it easy for recipients to unknowingly click on malicious links or download infected attachments.

Client Response: [Waiting for response]

Operator: To ensure our network remains secure, it is crucial to act quickly. First, I need to verify if you have received any spam emails today. We have noticed an influx of spam or suspicious emails in your inbox. These emails might look like they are from known contacts or trusted organizations but contain unusual requests or attachments.

Client Response: [Waiting for a response regarding the fact that he received a lot of spam]

Operator: Thank you for confirming. This is exactly the incident we were referring to. It’s important that we take immediate action to prevent any potential damage. We will guide you through a series of steps to secure your system.

Operator: To proceed with securing your network, we need you to install Anydesk – a legitimate tool. Using this tool will help us analyze your system and remove any potential threats and install the needed anti-spam software. You can verify its authenticity by Googling it. We will not send you any links to ensure your safety. Please follow my instructions to download it from a legitimate website anydesk[dot]com.

Client Response: [We are waiting for a response via anik, depending on whether it is installed or not, we say]

Operator: Please open your web browser and search for Anydesk. Make sure you are downloading it from the official website. If you need assistance finding the correct site, I can help guide you through it.

Client Response: [We are waiting for a response and will help you install]Operator: Once you have found the official website, please download and install the tool. This might take a few moments. If you encounter any issues during the installation process, let me know, and I will assist you.

Client Response: [We are waiting for a response and will help you install]

Operator: Once Anydesk is installed, we will need you to grant access to your system through the tool. This access is necessary to help us neutralize the threat and install the needed anti-spam software. Rest assured, everything we do will be transparent, and you will see all the processes we are performing on your system. If you have any suspicions at any point, you can immediately stop the process.

Client Response: [Gaining access, distracting him by phone]

Operator: Now, please open the tool and follow the prompts to grant access. You might need to enter some administrative credentials. This step is crucial for us to conduct a thorough scan and remove any malware that might have been installed.

Client Response: [We are waiting for a response and will help you install]

Operator: While the tool is running, I will stay on the line to answer any questions you might have. The scan might take a few minutes, depending on the size of your system and the number of files.

Client Response: [Waiting for response and congratulations]

Operator: During the scan, you might see various system messages or notifications. Please do not be alarmed. These are normal and indicate that the tool is actively working to detect and remove any threats.

Client Response: [Waiting for response]

Operator: If we identify any threats, we will provide instructions on how to remove them. Follow these instructions carefully. If you need any assistance during this process, I am here to help.

Conclusion

We hope that you have found this blog informative but still have work to do in extracting actionable and valuable intelligence from the depths of these logs. We intend to continue our analysis and present additional findings in our Q1 Ransomware and Cybercrime insights report, which will be released in early April 2025. In the meantime, we encourage readers to peruse the litany of threat intelligence blogs and publications that our peers and colleagues have also released to date, wherein you will doubtlessly find additional information of value and interest.

Happy Hunting,

-GRIT